As the climate crisis intensifies, its economic implications ripple across every corner of society. From shattered harvests to surging investment in green industries, understanding these dynamics is crucial for business leaders, policymakers, and communities worldwide.

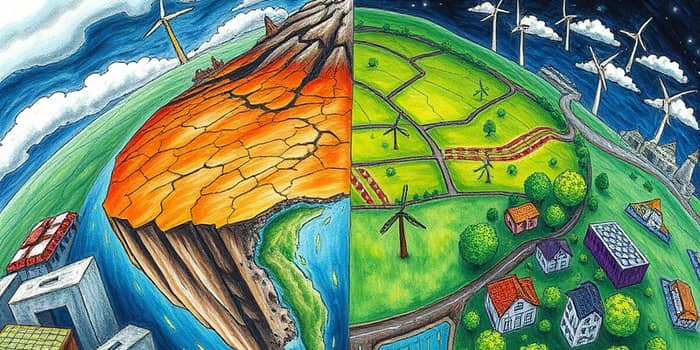

Climate change is far more than an environmental issue; it is a present-day economic disruptor affecting productivity and growth. Physical impacts—such as extreme weather events—intersect with transition dynamics, where policy and technology shifts redefine markets and livelihoods.

The intricate relationship between economic activity and environmental stability means that nations, industries, and communities must grapple with both immediate damages and the cost of long-term planning.

Global estimates paint a grim picture. Without urgent mitigation, annual damages to agriculture, infrastructure, health, and productivity could reach an astonishing $38 trillion a year by 2050. Historical emissions alone threaten a losses of 19% of income per capita within 26 years, effectively dragging millions into economic stagnation.

Sector-specific impacts reveal how unevenly these costs fall:

Climate change does not strike evenly. Low-income and developing countries, often located in heat- and climate-sensitive regions, bear the brunt with the least capacity to adapt. Over 1.2 billion people are at high risk from at least one critical climate hazard—be it heatwaves, flooding, drought, cyclones, or water stress.

Cascading effects amplify these challenges: disrupted supply chains, forced migration, and geopolitical tensions can emerge far from the original epicenter of a climate shock. As economic losses outpace GDP growth in many regions, inequality deepens both between and within nations.

While the risks are vast, so are the opportunities for innovation and growth. Evidence shows that the costs of climate damages already exceed mitigation expenses, making early action both fiscally and socially prudent.

Despite mounting evidence, barriers persist. Uncertainties in model projections and the distribution of impacts complicate planning. Political inertia and limited institutional capacity in many regions delay essential adaptation measures, widening the gap between action and need.

Ongoing research continues to revise loss estimates upward as more complex interactions—like global weather shocks—are incorporated into economic assessments.

Effective response demands international coordination on adaptation finance emissions and emissions reduction, ensuring equitable access to climate funds. Successive COP conferences have highlighted the urgency, yet commitments often fall short of the scale required to avert catastrophic outcomes.

Governments must align fiscal policy, regulatory frameworks, and public investment to support a just transition, particularly for vulnerable populations and regions.

Looking ahead, critical questions remain:

By reframing climate action as an engine for innovation and equitable growth, stakeholders can transform looming threats into opportunities for sustainable prosperity and resilience.

References